Leigh Crow Rewrote the Rules of Elvis and Drag with Elvis Herselvis

In the long shadow cast by Elvis Presley, imitation has always been both ritual and rebellion. Thousands of performers have donned the jumpsuit, curled the lip, and rehearsed the swivel. But in 1988, one performer didn’t just impersonate Elvis—she detonated the category entirely.

That performer was Leigh Crow, and her creation, Elvis Herselvis, would become the world’s first widely recognized female Elvis impersonator. Over the next three decades, Crow’s work would reshape drag culture, provoke cultural institutions, unsettle assumptions about masculinity, and quietly help reintroduce the term Drag King to a wider audience.

This isn’t just the story of an Elvis impersonator. It’s the story of how one artist used performance to expose the fragile scaffolding underneath cultural icons.

Becoming Elvis Herselvis

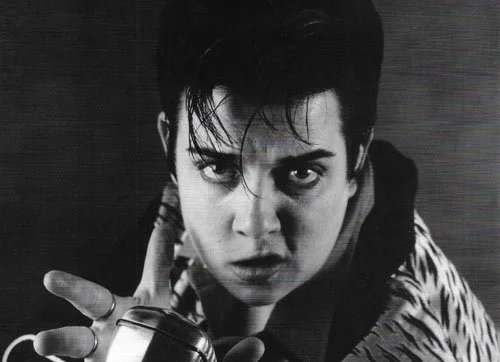

Leigh Crow was born on July 16, 1965—coincidentally Elvis’s birthday—and grew up in Phoenix, Arizona. At 24, she followed a flirtation to San Francisco, a city that, in the late 1980s, was fertile ground for radical performance and queer experimentation. That same year, she performed in her first drag show. The character she chose would define a generation of work: Elvis Herselvis.

From the beginning, Herselvis was not a novelty act. Crow approached Elvis as a fully embodied character study—voice, posture, swagger, sexuality—while deliberately refusing the illusion that gender performance was neutral or fixed. Where most Elvis impersonators aimed for reverence, Crow aimed for friction.

Backed by her live band The Straight White Males, Elvis Herselvis toured extensively, particularly in the American South. The act was raw, funny, confrontational, and musically convincing. Crow’s Elvis could croon with sensuous vibrato, mop sweat from her brow, and then puncture the fantasy by addressing Elvis’ drug use, sexual mythology, and cultural contradictions—all while staying completely in character.

Drag King Before the Term Had Weight

While drag queens had long occupied space in mainstream culture, drag kings were still largely underground in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Elvis Herselvis helped change that.

Crow’s work didn’t parody masculinity—it performed it too well. She understood Elvis not just as a singer, but as a hyper-masculine construct layered with glamour, vulnerability, and artifice. In her words, Elvis represented “one of the last bastions of masculinity—the right to ‘do’ Elvis.”

By occupying that space unapologetically, Herselvis unsettled straight audiences and electrified queer ones. Crow argued that Elvis already contained femininity: makeup, pink costumes, meticulous grooming, theatrical vulnerability. Herselvis didn’t distort Elvis—she revealed him.

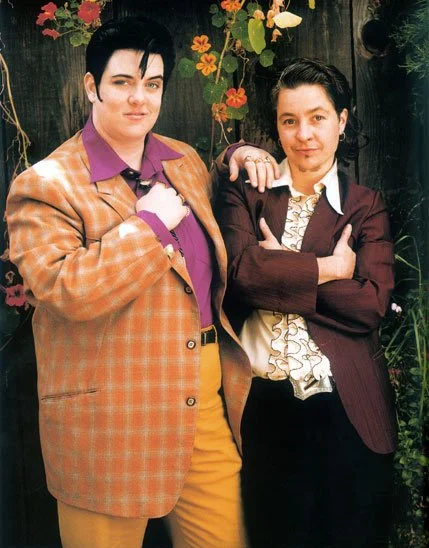

Elvis Herselvis & Elvis Emulator, 1997 (Photo courtesy of Del LaGrace)

When Graceland Pulled the Plug

The cultural stakes of Herselvis became national news in 1996, when she was invited to perform at the Second International Elvis Presley Conference at the University of Mississippi.

The conference organizer explicitly framed her inclusion as a test of race, class, sexuality, and cultural ownership. Local religious leaders protested. Political pressure followed. Then Graceland—via Elvis Presley Enterprises—formally withdrew funding.

The irony wasn’t lost on anyone paying attention. Elvis himself had faced intense moral panic, class anxiety, and censorship throughout his career. Herselvis was exposing the same fault lines decades later.

Rather than derail Crow’s career, the controversy cemented her reputation. She had proven that Elvis impersonation wasn’t neutral nostalgia—it was a contested cultural space.

Beyond Elvis: A Career of Shape-Shifting

Although Elvis Herselvis remained her most famous role, Leigh Crow never stayed in one lane for long.

In the early 1990s, she performed male roles with San Francisco’s The Sick and Twisted Players, staging camp parodies of classic films and TV shows. She also played in the new-wave revival band The Pleshettes.

By the mid-1990s, Crow was performing internationally, including the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras Arts Festival, and regularly appearing at Pride celebrations across California. Her first lesbian country band, Flatcracker, expanded her musical range and sharpened her interest in Americana through a queer lens.

In 1998, she co-founded the bubblegum pop cover band The Whoa Nellies, performing alongside the Gay Men’s Chorus and sharing stages with Joan Baez—proof that Crow’s career continually crossed genres, audiences, and expectations.

Rockabilly, Theater, and Cult Roles

In the 2000s, Crow joined the all-female rockabilly band The Mighty Slim Pickins, blending vintage sound with contemporary queer energy. At the same time, she deepened her theatrical work with San Francisco’s Hypnodrome Theater and The Thrillpeddlers, known for Grand Guignol and Theatre of the Ridiculous productions.

In 2011, Crow starred as Divina in Vice Palace, originally performed by Divine in 1972. Her performance earned a Bay Area Theater Critics Circle award—recognition not just of drag, but of serious theatrical craft.

Then came Captain Kirk.

In Star Trek Live at Oasis in San Francisco, Crow fulfilled a lifelong fantasy by embodying another hyper-masculine icon. Her Kirk was swaggering, absurd, erotic, and affectionate—earning a cult following and reaffirming her gift for finding the fault lines in cultural heroes.

That energy once led her, in full Kirk regalia, to surprise George Takei at the Twin Peaks Tavern during the filming of To Be Takei. She kissed him, ordered a bourbon, and walked off—a perfect encapsulation of her style.

Building Space for Others

In 2016, Leigh Crow and her partner Ruby Vixen founded Dandy Drag King Cabaret, a platform dedicated to elevating drag king performance. At a time when drag kings were still underrepresented, the show created visibility, mentorship, and community. It won Best Drag Show from the Bay Area Reporter in 2019.

Crow also co-founded the queer country band Velvetta, releasing original music and continuing to perform today. During the pandemic, when live performance disappeared, she turned to acrylic resin casting—creating bolo ties and pendants as another form of creative survival.

Elvis Herselvis Still Matters

Academic interest in Herselvis followed the culture. Music scholars have described female Elvis impersonators as “campy, cheeky, and disturbingly convincing.” That last phrase matters. Crow wasn’t simply parodying Elvis—she was inhabiting him in ways that revealed how unstable masculinity really is.

Elvis Herselvis didn’t diminish Elvis Presley. She expanded him.

More than thirty years on, Leigh Crow remains a working artist, a mentor, and a boundary-pusher. Her career demonstrates that impersonation can be critique, drag can be scholarship, and performance can expose truths that institutions would rather keep buried.

Elvis may have left the building—but thanks to Elvis Herselvis, he never stopped changing shape.

The song’s melody didn’t originate with Presley. It’s based on the Italian classic “’O Sole Mio,” written in 1898 by Eduardo di Capua, a melody already familiar across Europe and the United States. In the late 1950s, Elvis first heard a version of it while stationed in Germany — specifically the 1949 adaptation “There’s No Tomorrow” by Tony Martin — and became captivated by its dramatic sweep.

He shared the idea with his music publisher, Freddy Bienstock. Bienstock quickly brought in songwriters Aaron Schroeder and Wally Gold, who wrote the English lyrics that would transform the melody into “It’s Now or Never.” According to accounts, the lyrics were completed in about 30 minutes, illustrating how sometimes the most iconic songs can emerge rapidly from creative inspiration.