Andy Kaufman’s Elvis: A Tribute Act While the King Was Still Alive

Elvis impersonators are now a cultural cliché. They populate Las Vegas sidewalks, wedding chapels, cruise ships, and county fairs. Most exist in a world that only became possible after Elvis Presley died—when impersonation shifted from audacity to homage, from risky to safe. Andy Kaufman’s Elvis impersonation belongs to an entirely different category. He didn’t perform Elvis as nostalgia. He performed Elvis while Elvis was still alive, still famous, still touring, still capable of watching someone else step into his silhouette.

That timing alone makes Kaufman’s Elvis remarkable. But the deeper significance lies in how and why he did it—and what that says about identity, fame, comedy, and obsession in America.

An Impression Hidden Inside Another Act

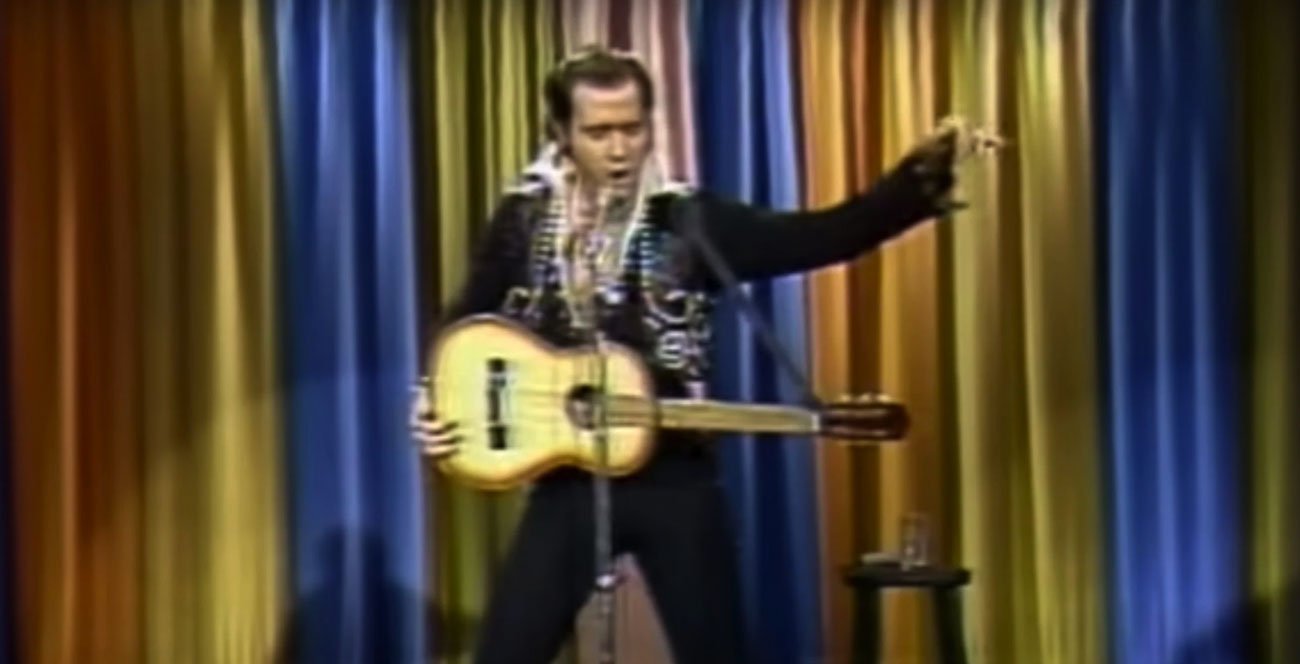

Andy Kaufman never walked onstage announcing himself as an Elvis impersonator. Instead, he concealed Elvis inside something else. Often, Kaufman appeared as a timid, awkward character with a vague foreign accent—telling jokes that landed flat, delivering intentionally bad celebrity impressions, and lowering audience expectations to nearly zero. Then, without warning, the character would turn his back, adjust his hair, shrug off a jacket, and re-emerge as Elvis Presley.

The transformation was immediate and jarring. The voice snapped into place. The posture changed. The room changed.

This wasn’t parody. It wasn’t mockery. It was competence revealed all at once, almost violently. The laugh didn’t come from making fun of Elvis—it came from the shock of realizing that the strange, halting figure the audience had dismissed moments earlier was capable of channeling one of the most powerful stage presences in American history.

Kaufman used Elvis not as a punchline, but as a reveal.

Doing Elvis While Elvis Was Still Alive

The fact that Kaufman performed this act publicly in the 1970s—before Elvis Presley’s death in August 1977—is crucial. Today, During Elvis’s lifetime, impersonation was risky. The performer could have ben interpreted as disrespectful.

Kaufman appeared on major television platforms performing Elvis while Presley was still alive, including appearances in 1977. That placed Kaufman in a narrow historical window: famous enough to be seen by millions, bold enough to impersonate a living icon, and strange enough to do it without explanation or apology.

Was Andy Kaufman the First Elvis Impersonator?

No—at least not in a literal sense. Elvis impersonation existed during Presley’s lifetime, and historians often point to performers like Bill Haney as the earliest full-time Elvis impersonators. Kaufman did not invent the idea of doing Elvis.

What he did invent—or at least popularize—was the conceptual Elvis impersonation. He wasn’t building a career around looking like Elvis. He wasn’t selling the fantasy of “Elvis lives.” Instead, he used Elvis as a tool to manipulate audience perception: to expose how quickly charisma can overwrite doubt, and how fragile identity really is.

Kaufman wasn’t trying to replace Elvis. He was showing how easily Elvis could be summoned.

What Did Elvis Think?

Stories about Elvis’s reaction to Kaufman’s impersonation have circulated for decades. According to people close to Kaufman, including his brother, Elvis reportedly enjoyed Andy’s performance and considered it among the best he had seen. The explanation often given is telling: Kaufman was said to be the only impersonator who approached Elvis with genuine humor rather than imitation for its own sake.

There is no recorded interview where Elvis confirms this on the record, and that ambiguity matters. Kaufman thrived on myth. But the consistency of the story—and the reasoning behind it—rings true. Kaufman didn’t drain Elvis of mystery. He didn’t freeze him into caricature. He treated Elvis as something powerful, almost dangerous, something that could overtake a person.

If Elvis did appreciate Kaufman’s act, it’s likely because Kaufman wasn’t trying to be Elvis permanently. He was demonstrating what Elvis represented.

Why Kaufman Did It: Devotion, Not Irony

Andy Kaufman’s relationship with Elvis wasn’t ironic. It was emotional, bordering on devotional. As a young man, Kaufman hitchhiked to Las Vegas hoping to meet Elvis. He wrote letters expressing a belief that meeting Presley would be a defining moment in his life. Elvis wasn’t just a celebrity to Kaufman—he was a symbol of transcendence.

In Kaufman’s own recollections, Elvis represented transformation: the ability to step out of anonymity and command a room through sheer presence. That idea obsessed Kaufman. His entire career revolved around destabilizing expectations—refusing to explain himself, refusing to reassure audiences, refusing to deliver conventional punchlines. Elvis, paradoxically, allowed him to do the opposite for a moment: to give the audience exactly what they wanted, perfectly executed.

But even that generosity came with a twist. By placing Elvis inside a frame of awkwardness and anti-comedy, Kaufman revealed how much of charisma is context—and how fast we surrender to it once it appears.

Elvis as Metamorphosis, Not Mockery

Most impressions exaggerate flaws. Kaufman’s Elvis did not. It functioned more like a possession than a joke. The comedy wasn’t “look how silly Elvis is.” The comedy was “how did this person just become that person?”

That distinction matters. Kaufman treated Elvis with seriousness, even reverence. The act carried risk: if the impression failed, the entire routine collapsed. But when it succeeded, it felt less like comedy and more like witnessing a switch flip inside a human being.

Kaufman wasn’t laughing at Elvis. He was demonstrating Elvis’s gravitational pull.

Jim Carrey portrayed Kaufman in Man on the Moon (1999), recreating the moment where Kaufman himself transforms onstage into Elvis.

The Deeper Meaning: Identity, Fame, and Control

Kaufman’s Elvis impersonation works because it sits at the crossroads of several American fixations:

Fame as a kind of magic — Elvis embodied the belief that presence alone can elevate a person above ordinary life.

Identity as performance — Kaufman showed that who we are can change instantly, depending on posture, voice, and confidence.

Audience complicity — The crowd wants to believe. Kaufman proved how little evidence is required.

By giving audiences a flawless Elvis impression after denying them conventional entertainment, Kaufman wasn’t just performing—he was conducting an experiment. He was testing how quickly people would abandon skepticism once authority entered the room.

Why This Still Matters

Andy Kaufman’s Elvis impersonation endures because it resists easy classification. It isn’t stand-up in the traditional sense. It isn’t parody, and it certainly isn’t a conventional tribute. It sits closer to performance art—using comedy as a delivery system rather than a destination.

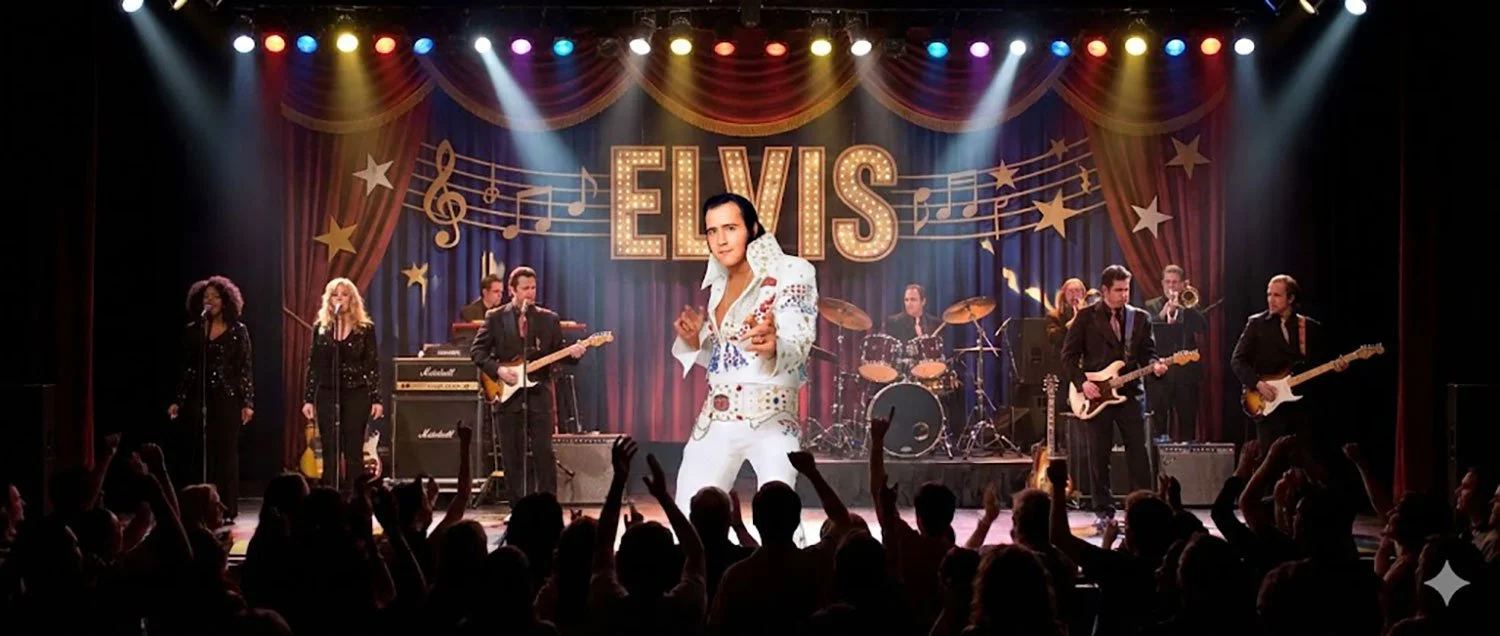

That idea was reinforced decades later in Man on the Moon (1999), the biographical film about Kaufman starring Jim Carrey. The movie treats Kaufman’s Elvis not as a throwaway gag, but as a defining moment of transformation. When Carrey recreates the Elvis reveal—shifting from Kaufman’s awkward, halting persona into a fully confident Presley—the film underscores what the act really was: a sudden assertion of power, control, and identity. Elvis isn’t played for laughs alone; he’s portrayed as the moment Kaufman seizes the room.

Importantly, the film frames the Elvis impersonation as sincere, not ironic. That mirrors reality. Kaufman’s Elvis wasn’t about mocking celebrity; it was about tapping into it. The movie makes clear that Elvis represented something Kaufman both revered and studied—a symbol of what it meant to command attention absolutely. In that sense, Man on the Moon helps modern audiences understand why the impersonation mattered at all: it wasn’t a bit, it was a breakthrough.

And the most critical fact remains unchanged, even in cinematic hindsight: Kaufman did this while Elvis was still alive. That single detail prevents the act from becoming quaint or nostalgic. It grounds it in risk. It reminds us that Kaufman wasn’t honoring a fallen legend—he was engaging directly with a living, dominant cultural force.

In today’s world, where impersonation has become an industry and a commodity, Kaufman’s Elvis still feels unsettling because it wasn’t safe. It didn’t explain itself. It didn’t ask for approval. As the film suggests, Kaufman wasn’t trying to make audiences comfortable—he was testing how far transformation could go before people stopped questioning it.

Whether seen on a 1970s television stage or reinterpreted through Jim Carrey decades later, Kaufman’s Elvis remains the same strange, powerful gesture: a brief occupation of the most iconic image in American pop culture, followed by a clean exit—leaving the audience unsure of what they witnessed, and why it worked so completely.